What the Chevron ruling means for the next US president

The Supreme Court weakened regulators and created uncertainty, inviting a “tsunami of lawsuits”

THE QUESTION confronted by the Supreme Court in Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo—whether the Magnuson-Stevens Act of 1976 implies that herring fishers in the Atlantic can be forced to pay the salaries of federal inspectors riding on their boats—might appear to be, well, small fry. Yet while the Supreme Court issued many consequential decisions this term, Loper Bright may turn out to be the most important of the lot.

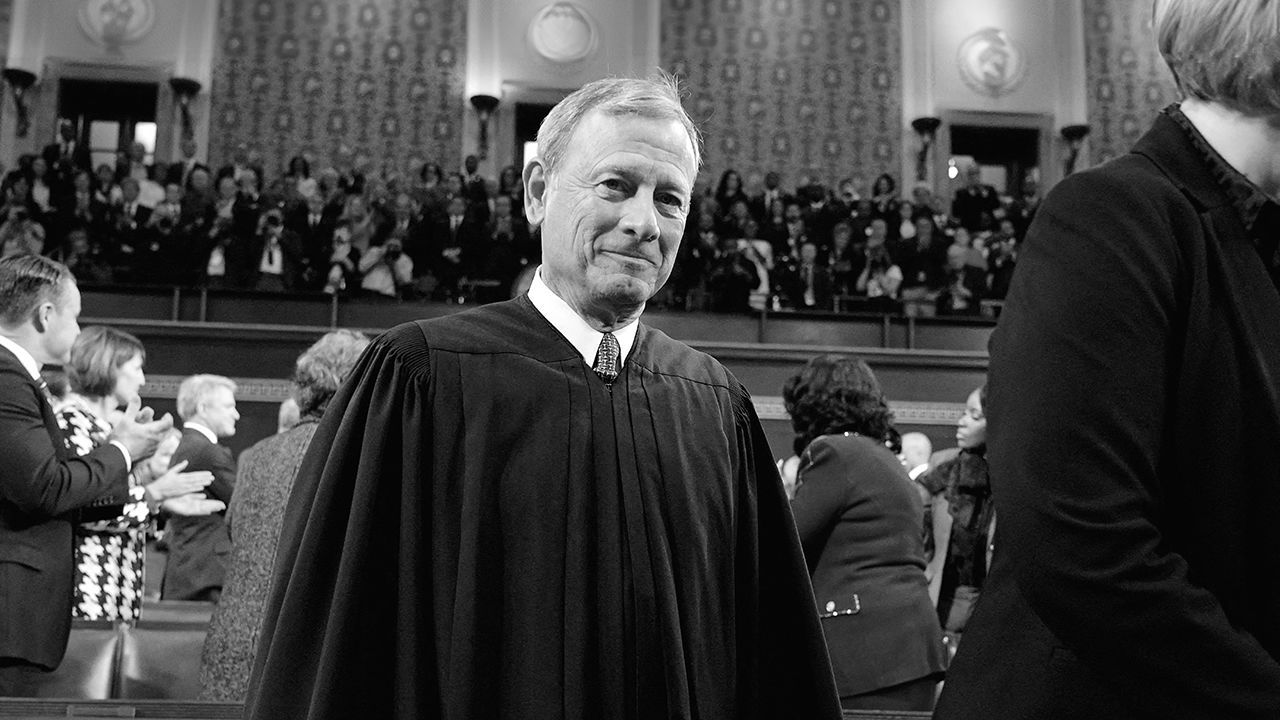

That is because the court’s conservative 6-3 majority used the case to strike a mighty blow against the American administrative state. Its ruling on June 28th eliminated a precedent called “Chevron deference”, named after a landmark case from 1984, that instructs courts to defer to federal agencies when their authority is left ambiguous by a law (as it frequently is). For decades, Chevron justified countless rules and regulations; under it, agencies and bureaucrats in charge of environmental, labour and financial matters made expansive use of the vague authorities delegated to them by Congress.

Explore more

This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline “What the Chevron ruling means”

More from United States

The demise of an iconic American highway

California’s Highway 1 is showing the limits of man’s ingenuity

How the election will shape the Supreme Court

A second Trump administration could lock in a conservative supermajority for decades

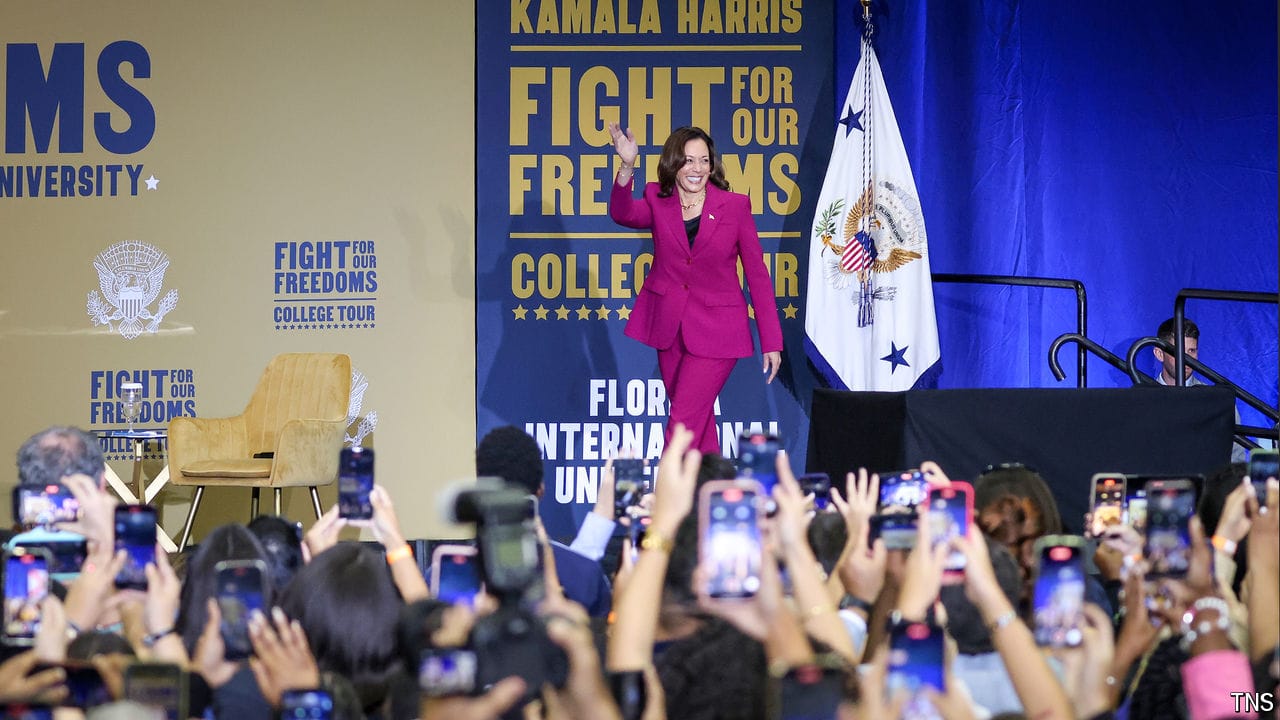

Could the Kamala Harris boost put Florida in play for Democrats?

Some party enthusiasts think so, but realists see re-energised campaigning there as a savvy Florida feint

America is not ready for a major war, says a bipartisan commission

The country is unaware of the dangers ahead, and of the costs to prepare for them

The southern border is Kamala Harris’s biggest political liability

What does her record reveal about her immigration policy?