The unsteady comeback of the California condor

The bird’s plight is a study in unintended consequences

IT MAY HAVE been the smelliest job in conservation. Whoever drew the short straw sat in a hole in the dirt underneath a carcass. Then they waited for a California condor to come and have a snack. “That’s not a pretty job at all,” says Chandra David, an animal keeper for the Los Angeles Zoo. “When a bird would land somebody would radio in saying ‘Now!’ and they would reach up and grab the bird’s legs.” This, and other less nauseating methods, is how the last remaining condors were brought in from the wild in the 1980s.

Californian condors are a species of vulture; they feed on dead animals. Adults can have a wingspan of up to three metres, making them the largest land bird in North America. As America’s population grew in the 19th and 20th centuries, the birds’ numbers plummeted. They were placed on the federal endangered-species list in 1967, but they continued to die off. Their near-demise, and recent comeback, provide a study in unintended consequences.

Explore more

This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline “Vulture capital”

More from United States

The demise of an iconic American highway

California’s Highway 1 is showing the limits of man’s ingenuity

How the election will shape the Supreme Court

A second Trump administration could lock in a conservative supermajority for decades

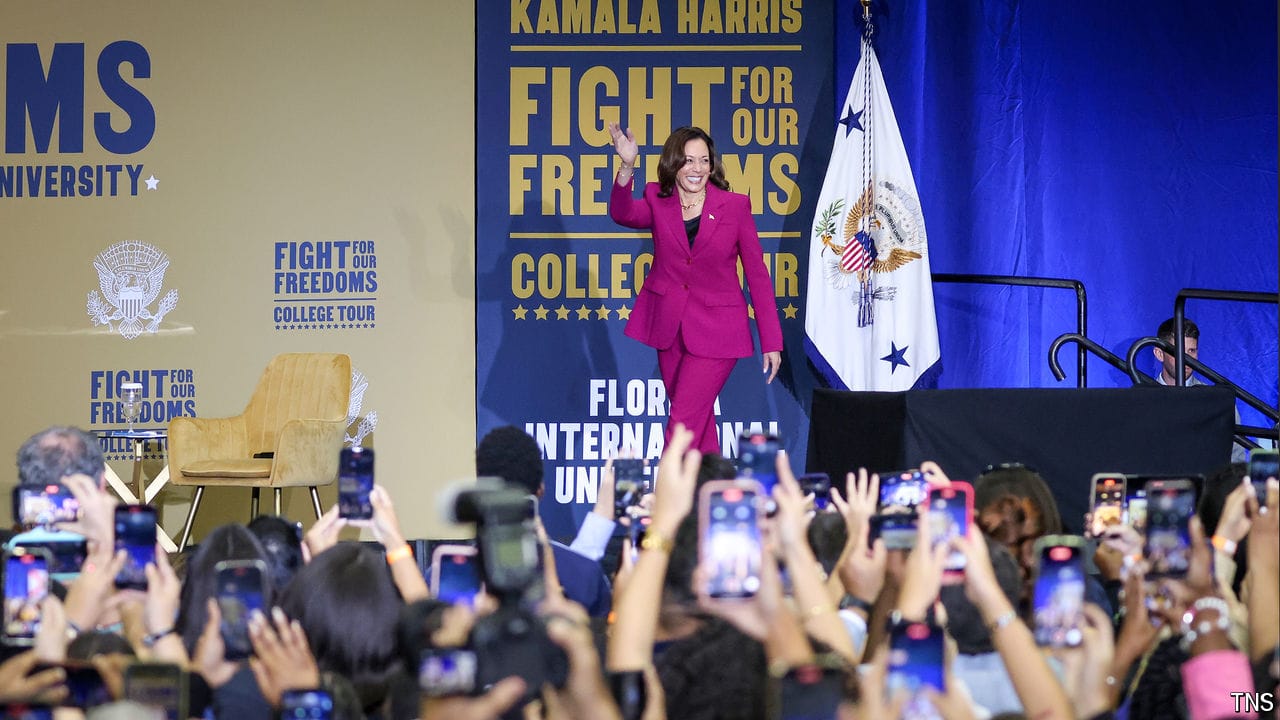

Could the Kamala Harris boost put Florida in play for Democrats?

Some party enthusiasts think so, but realists see re-energised campaigning there as a savvy Florida feint

America is not ready for a major war, says a bipartisan commission

The country is unaware of the dangers ahead, and of the costs to prepare for them

The southern border is Kamala Harris’s biggest political liability

What does her record reveal about her immigration policy?