Freeze-dried chromosomes can survive for thousands of years

They contain unprecedented detail about their long-dead parent organisms

For palaeontologists, DNA is infuriatingly fragile. Its long chains begin to break apart shortly after death, destroying valuable information about the deceased parent organism. Unlike bones, footprints and even faecal matter, which can comfortably survive—in fossilised form—for millions of years, DNA rarely lasts much more than a hundred. In recent decades scientists have discovered that some exceptionally well-preserved bodies do still have readable fragments of genetic code hundreds of thousands of years after death. But these have been tiny scraps. They lack much of the valuable information that an intact genome provides.

A major advance may be at hand. A new paper in Cell, a scientific journal, describes the discovery of fossil chromosomes—coiled-up strands of DNA millions of base pairs long—inside the cells of mammoths that died tens of thousands of years ago. The research “really opens a door for a new kind of exploration of ancient life”, says Erez Aiden of the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) in Houston, Texas, who is one of the paper’s lead authors.

This article appeared in the Science & technology section of the print edition under the headline “Uncut and dried”

More from Science and technology

How Ukraine’s new tech foils Russian aerial attacks

It is pioneering acoustic detection, with surprising success

The deep sea is home to “dark oxygen”

Nodules on the seabed, rather than photosynthesis, are the source of the gas

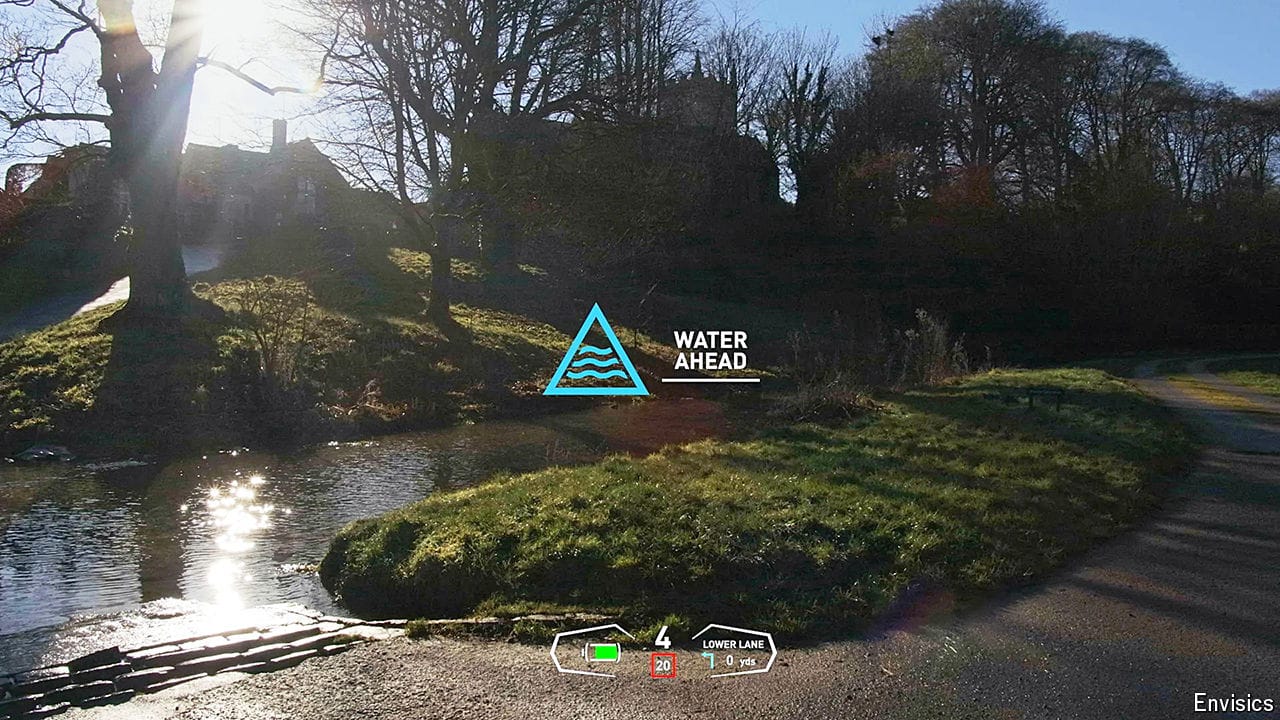

Augmented reality offers a safer driving experience

Complete with holograms on the windscreen

Clues to a possible cure for AIDS

Doctors, scientists and activists meet to discuss how to pummel HIV

AI can predict tipping points before they happen

Potential applications span from economics to epidemiology

Astronomers have found a cave on the moon

Such structures could serve as habitats for future astronauts