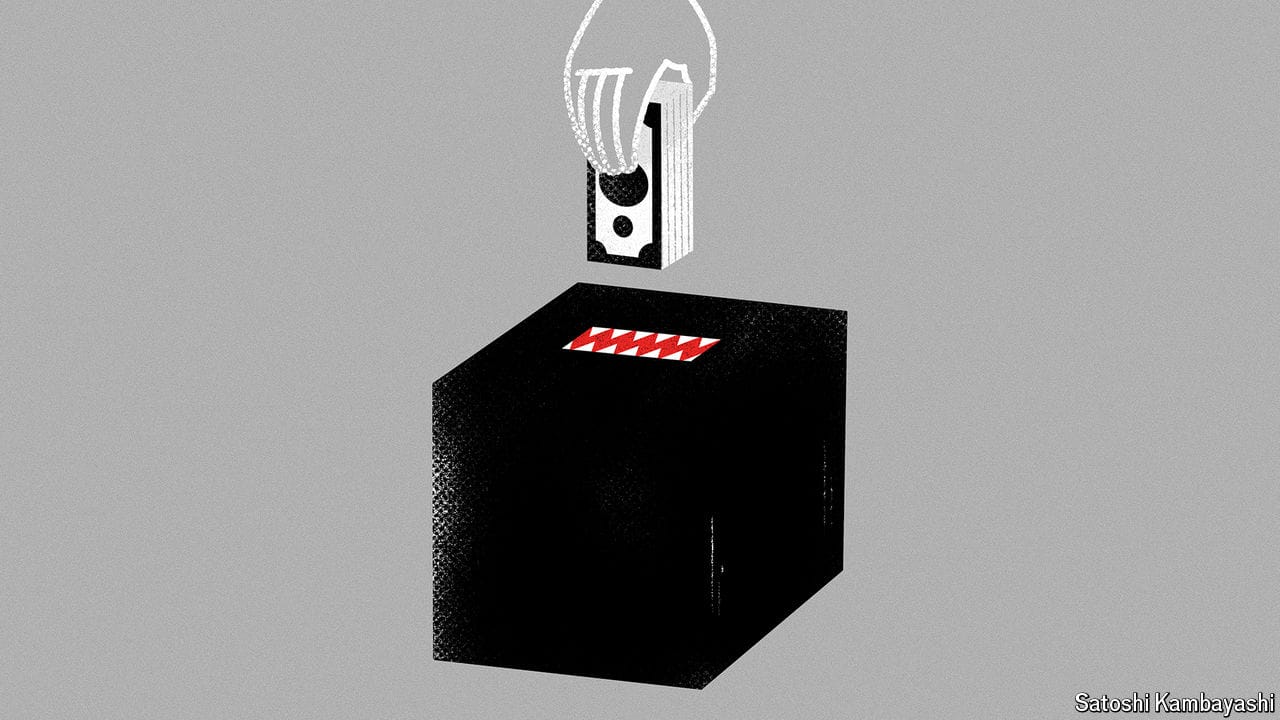

Bubble-hunting has become more art than science

With the usual gauges of frothiness out of action, behavioural signals are all investors have

UPON BEING sucked into investing during the South Sea Bubble, Sir Isaac Newton reflected that he could “calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies but not the madness of people”. From tulip mania in 17th-century Amsterdam to railway fever in Victorian Britain, history is littered with tales of investors who lost their heads shortly before they lost their shirts, in the grip of mass delusions described by Alan Greenspan, a former chairman of the Federal Reserve, as “irrational exuberance”.

These delusions seem obvious with the cold clarity of hindsight. Spotting them in real time, however, is trickier—especially when the usual measures of frothiness are out of action. Wall Street types typically pore over price-to-earnings ratios, which compare a firm’s value with its profits, or free-cashflow measures, which look at the cash firms crank out after investment. Warren Buffett targets firms with a high return on capital, which compares their profits with the size of their balance-sheets. But the covid-induced economic slump has caused earnings to sink even as the Fed and other policymakers have helped buoy share prices. The obvious gauges of frothiness are not much use.

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the headline “Foam party”

Finance & economics August 22nd 2020

More from Finance and economics

China’s last boomtowns show rapid growth is still possible

All it takes is for the state to work with the market

What the war on tourism gets wrong

Visitors are a boon, if managed wisely

Why investors are unwise to bet on elections

Turning a profit from political news is a lot harder than it looks

Revisiting the work of Donald Harris, father of Kamala

The combative Marxist economist focused on questions related to growth

Donald Trump wants a weaker dollar. What are his options?

All come with their own drawbacks

Why is Xi Jinping building secret commodity stockpiles?

Vast new holdings of grain, natural gas and oil suggest trouble ahead