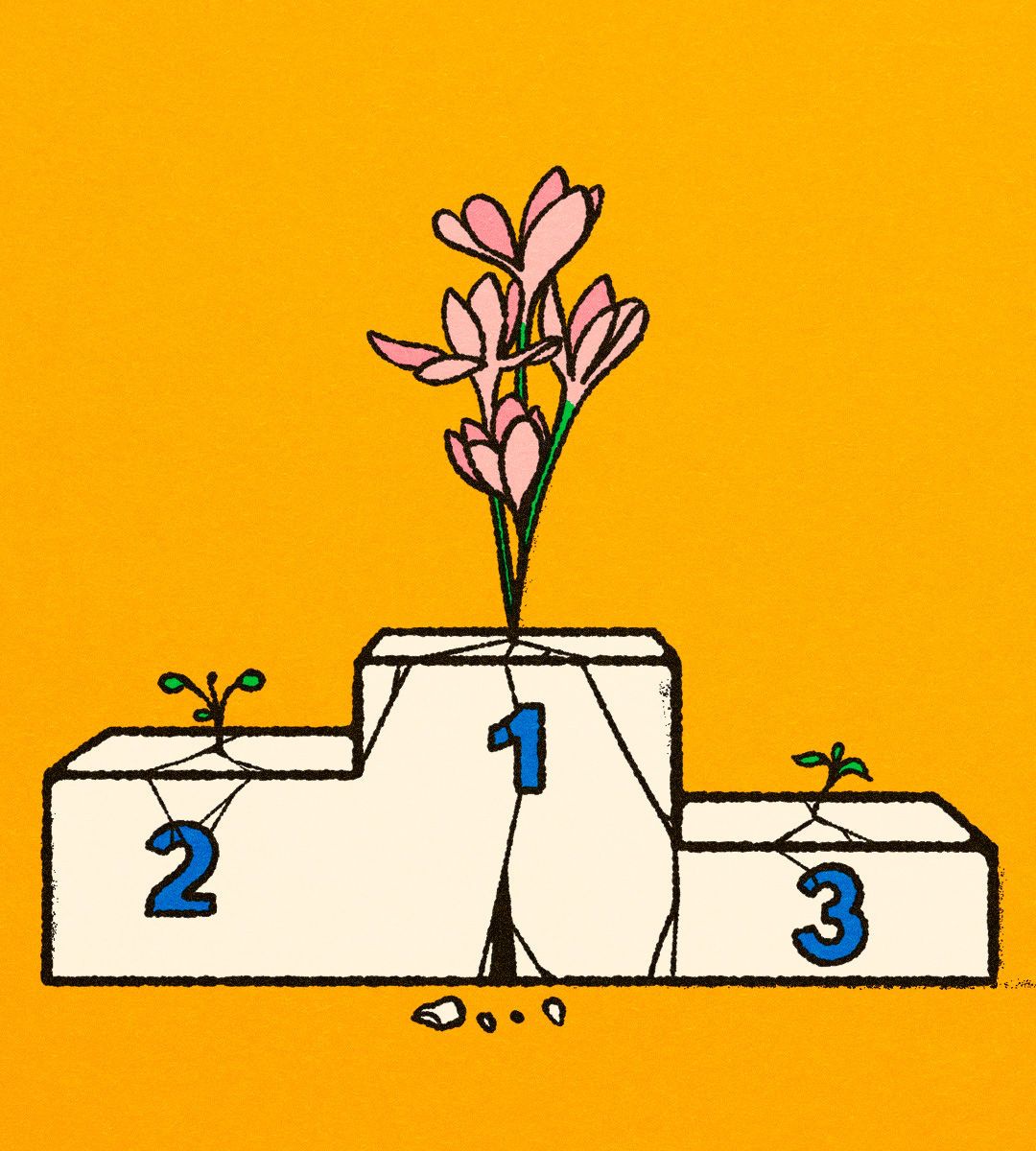

The green transition will transform the global economic order

But the winners and losers are not as obvious as you might think

By Matthieu Favas

The transition to a carbon-neutral world should make all countries better off, at least in theory. Many will rely less on fuel imports, yielding big savings and insulating their economies from swings in hydrocarbon prices. Those that export the metals needed for new Teslas, turbines and terawatt-hours of grid capacity will earn juicy rents. Even former petrostates may thrive if they can use revamped refineries and pipelines, as well as wind and sun, to make hydrogen. And everyone would welcome a planet that stops getting hotter and more dangerous every year.

In practice, the transition to net zero will be turbulent. Changing energy-consumption patterns and the reshuffling of trade flows will both crown new winners and create new losers. In 2024 this divergence, hitherto masked by the effects of covid-19, a flagging global economy and China’s deceleration, will start to become more visible—but not always in the ways you might expect. It is not simply the case that providers of fossil-fuel resources will lose and providers of green resources will win. There will be winners and losers in both camps.

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Transfer window”